Staff writer

At the turn of the Millennium, some people turned to an apocalyptic vision of the end times, announcing the number 2000 as an obvious sign of the world’s imminent end. Computer software designed with two-digit year dates was re-programmed to prevent a return to 00. Surely, here was a sign that the time was right to ‘re-set’ all the conditions that denied the realisation of wealth creation, by deleting in-built obsolescence linked to the inconvenience of ageing? In England and Wales, the Catholic Bishops published a document calling on the richest nations to reset unpayable debts for those nations least able to repay. Governments around the world committed to the Millennium Development Goals on a road to ‘end poverty’.

In the most recent incarnation of these targets, the Sustainable Development Goals (2015-30), governments have set targets to ‘end poverty’ everywhere by 2030. A positive reading of this goal might be that each of us will have removed barriers to the fulness of life of each person; a social order will have been established enacting a global common good for everyone and all societies. The ‘end poverty’ carrot is accompanied by a stick. If you do not end poverty, the world will end because of irreversible climate change – and in the most assertive predictions, 2030 is about the time the apocalypse will happen. Both visions – the devastated earth and the impossibly indebted – have many echoes in human history and what is represented in our tradition as a prophetic voice compatible with reason. People have long tried to tie these visions to an identification of God’s action and a treatment of others as objects of both ‘development’ (which many see as colonisation/forced culture change) and ‘charity’.

The Twentieth Century had more than its share of -isms in which prophetic voices of the Left and Right promised an end to all sorts of deficiencies. All of them deny the dignity of the person. Ending poverty could mean killing people whose physical and mental condition did not fit into a dominant idea of productivity, or who were deemed to be inept because of their race, colour and age. This pattern remains alive and well on our doorstep, perhaps even in our own household’s uses of time and space – think of the mass buy-in to a view of the ‘body beautiful’, and the ways in which the beloved NHS and welfare system have to work through very complex questions of prioritising treatments and benefits in relation to perceived scarcity of resources and calculated economic return.

These are vast topics, and I want to focus simply on how we might more authentically give voice to the message that we can ‘end poverty’.

Pope Francis’s focus on a world that is ‘of’ the poor, in other words what belongs to the people, is not utopian, resigned to apocalyptic language or genocide. It seems first and foremost a recognition that the vast majority of humanity’s experience is what the richest among us term ‘poverty’. ‘Reality’, he says, ‘is greater than ideas’. We may entertain all kinds of ideas of what ‘end poverty’ means, but those who would ‘end’ it might be more informed by finding some way to go and live among the ‘poor’. If you do this freely, you will discover that your ideas of the person and of poverty will change in surprising ways. ‘Time’, he says, ‘is greater than space’. In the ‘poor’ there is often a great deal of time, more than the materially rich would like to put an ‘end’ on it through campaigns and targets. The witness of religious congregations and charities in the Caritas network, in the struggle between what people will support (including by tied grants and donations) and embodied commitment to the long haul, is where this testing for time seems particularly fierce and – on the face of it – loaded in favour of the impatient, those who want their end now. It is the front line of working out forms of social evangelisation that are harmonious locally and nationally, and with the reality of the polity we have.

The truly penitent person, through the eyes of an ‘end to poverty’, then, should surely be more than one who sets another campaign, target or project. ‘Unity’, Pope Francis explains, ‘is greater than conflict’. It’s a way of addressing the objectification, unkindness and division that are rampant not only in politics, but within even the practices of charity, and what it looks like to be church today among many committed people in structures that reinforce our fragmentation and the multiplication of contractual knots.

In a Catholic understanding, the penitent person recognises and accepts the need to be in right relationship with God and the world. The penitent asks to be absolved, in a deepening encounter with the free gift of life, in the being of an abundant Creator. Absolution comes straight from the Latin verb, solvere, meaning to untie (loosen, release). In an interior sense, the penitent stands naked before God, and asks to be untied from wrongful relationships. The penitent’s intention, growing in hope, is less to be free from the end of something, and rather freer to become fully the person God is patiently waiting to bless, all in all. This blessing, of satisfaction – being with what is enough – has as signs both (tangible) restoration and faith (however dimly recognised) in forgiveness.

One of the commitments for Christians daring to offer voice and action in the service of charity, is to ask God to enlighten more clearly the ways in which this praxis is integrated with faith and hope. It is important to recognise that there are abuses to the person and to creation that must be stopped. But in many policy contexts, telling people exactly what they must do, and promising an end to poverty in specific timescales, seem ripe for co-option into all kinds of ideologies that are a long way from both a life-giving faith and hope, and the dignity of the person in relationship to others.

If we accept that a human is made good, endowed with so many gifts that are more or less waiting to be fanned into flame, then it is our ability to ‘solve’ in person and together, rather than making an ‘end’, that allows each person the full dignity we celebrate. To do this in person, Pope Francis argues, requires genuine encounter. To solve together any structural oppression of the majority of humanity by a minority, requires a growing ability, most of all among those who consider themselves rich, to organise activities and structures in a way that accepts all is gift. To solve together means to bring into creative participation the loosening of contractual bonds of utterly insoluble debt, and the uses of capital, land and property tenure that stunt true growth by focusing on getting, and keeping for my own ends, more than I or my society (e.g. household, church, organisation, state) needs. Proclaiming an end to that process denies the state of a humanity on the journey back to a God who is.

The views expressed in this blog are of the author and not CSAN policy.

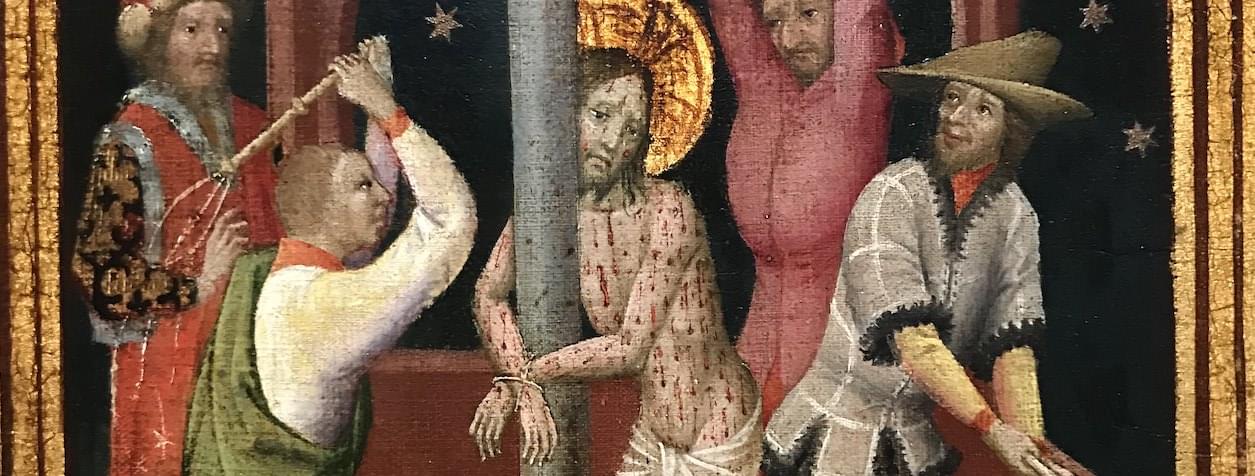

Picture: The Scourging of Christ (cf. John 18:12, 19:1). Credit – genibee.