On Easter Monday morning, we woke up to the news that Pope Francis had died. The news came as more of a shock than I expected. The Pope had not long returned home after a long stay in hospital during which, by all accounts, he was close to death more than once. He appeared in public on Easter Sunday – against the advice of his doctors – blessed the crowds and then toured St Peter’s Square in the Popemobile. He looked ill and pained. Now we wonder what that last public appearance took out of him. We knew he was very ill, but still the news of his death was a shock, just like it is still a shock to hear of the death of a much-loved family member who is old and at the end of life. The conversation stops. We will never again hear that voice in real time, enjoy that smile. It is the jarring difference between presence one day and absence the next. We refer to them in the past tense.

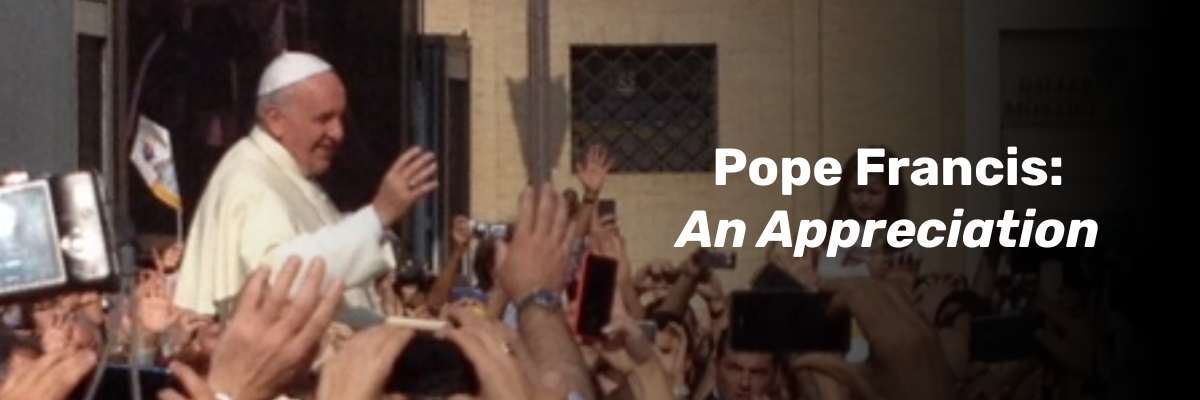

As we come to terms with his loss, there will be much reflection on the legacy of Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the first pope from Latin America who asked the world to pray for him when he appeared on the balcony of St Peter’s on 13 March 2013 as Pope Francis. I first saw him a few months later in St Peter’s Square as he was driven through the crowds, unprotected by security shields, waving and smiling, wanting to be close to people, a hallmark of his papacy. The atmosphere was charged and emotional. Within a few short months, the new pope had touched the hearts of millions by his desire to touch the suffering flesh of humanity, in which he saw the face of Christ.

Another hallmark of his papacy was his significant contribution to the Church’s social doctrine, that corpus of papal encyclicals which began in the modern era when Pope Leo XIII issued Rerum Novarum, the Church’s reading of the signs of the times in the late nineteenth century, in particular the degrading effects of industrialisation on the dignity of workers and their families. Since then, subsequent popes have asked the same questions: what is going on in society, what is the Gospel telling us about what we see, and what can we do to build a more just world? In 2015, Pope Francis issued a landmark social encyclical, Laudato Si’, the first encyclical to be devoted entirely to the climate crisis. Like any prophet, he challenged us. He urged us to an ecological conversion, a change of heart and a re-setting of our relationship with God, our brothers and sisters, and creation itself. Strikingly, he called for us to be reconciled with nature. The encyclical continues to have a profound effect on the lives of Catholics, in our homes and parishes, schools and charities; and indeed well beyond the Church. The letter was addressed to all people of good will.

His other major contribution to Catholic social teaching was his 2020 encyclical, Fratelli Tutti (“Siblings All”). Here he was reflecting on the disastrous effects of the Covid pandemic, but looking deeper at the issues which the pandemic exposed and calling for a return to the Gospel: to the building of bridges, not walls; a culture of encounter, not indifference; an economy that cares, not an economy that kills. Throughout, he kept insisting on what he saw as the heart of the Gospel, God’s love for those who are made poor by injustice, for those who live on what he called the peripheries. This is where we will find God, he reminded us. When he initiated the largest listening exercise in human history – in the synod – he encouraged us to pay particular attention to the voices of those on the margins of society.

His teaching has been an inspiration to the Church and those in the Church – like the 165 Caritas national agencies worldwide, or the 50 Catholic charities in England and Wales that make up the Caritas Social Action Network – who work on the front line of human suffering and exclusion. He was always clear that action for social justice, to build the bonds of social friendship in the face of division, was a core part of the Gospel. In his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, he said, “An authentic faith – which is never comfortable or completely personal – always involves a deep desire to change the world, to transmit values, to leave this earth somehow better that we found it.” (#183)

I met Pope Francis in person in May 2023 at an audience for the leaders of the Caritas global network. Around five hundred of us gathered in the marble-lined splendour of the Clementine Hall in the Vatican. Our audience was due to begin at 12 noon. There was a loud murmur of conversation as we waited, until someone said, “It’s the pope!” Without any fanfare or announcement, Pope Francis walked into the room. We shuffled quickly to our feet, taken aback. He gestured us to sit and sat down himself. He was holding a ten-page speech, “but you can read that later,” he said in Italian, handing the pages to a cardinal. He spoke off-the-cuff for a minute or so about Caritas – God’s love among us – then spent the rest of the audience shaking the hand of every single person in the room.

I was sitting beside one of our bishops. “Watch what he’s doing,” he said. “He’s teaching us.” What Pope Francis was teaching us what that reality is more important than ideas, that the art of encounter – the art of God made flesh in Jesus – is about closeness, warmth, attention. In our communities, that encounter leads to accompaniment – another favourite word of Pope Francis – to social friendship, and a desire to advocate for social justice. While I was waiting my turn to shake the pope’s hand, I was wondering – as we all were, it turned out – what I might say to him. In the end I settled on a few simple words which now sum up my feelings for this remarkable papacy, “Grazie, Papa Francesco.”

Raymond Friel

You must be logged in to post a comment.